1. Introduction

You are going to have real fun here. And, you will gain the ability to do impressive things in life using a computer. It will be like acquiring a superpower to be able to do things that ordinary people cannot do. Let’s see how that is possible.

A common mobile device, the one you might have in your hands right now, can have 100,000 times more computing power than the computer used to send humans to the moon for the first time. There are 7.7 billion humans; did you know that by 2020 there will be more than 30 billion devices connected to the Internet? Imagine all that power… you could do many unprecedented things with only a little part of it, and that power keeps growing everyday…

Our world depends on computers. Imagine the apocalyptic catastrophe if computers ceased to work: money in banks is inaccessible, all telecommunications die, airports cease functioning and commercial airliners would fall from the sky, energy distribution systems become uncontrollable, hospitals and critical life support systems would irrevocably fail, and our society would collapse. In 1988, a single person, without bad intentions, took down all the Internet with just one malicious program, known as the Morris Worm. Society was different at that time so it was not as catastrophic as it would have been now. But, why we have not collapsed yet?

The only way to overcome a weakness is to first know that it exists. Hackers find weaknesses in the computer world. The word hacker has had several definitions throughout history. In a dictionary, we can find two related definitions:

-

An expert at programming and solving problems with a computer

-

A person who illegally gains access to and sometimes tampers with information in a computer system

We are going to take a little from both definitions, but we will gain access and tamper with information for good. In other words, a skill can be used for malicious purposes or, to become the real-life hero that manipulates technology at will, keeping the planes in the sky, and society out of collapse. That sounds romantic, but you will realize that just the mere fact of making your computer make something awesome, and getting a secret flag generates emotions and adrenaline. Come with us on this journey to become a real hacker!

2. The Shell

Luke Jones

The Shell is foundational to so many parts of securing computing devices and their networks. Intimidating and alluring (like most symbols enshrined by film makers), understanding the shell can make or break one’s ability to solve challenges in a capture-the-flag competition like picoCTF.

To be transparent, I (LT) am still learning a lot about the shell, and I’m just about 10 years into it right now! This is an encouragement - anyone curious enough to jump into rabbit holes here and there is always going to have opportunities to learn more about an amazing tool like the shell. But rest assured, I was proficient in the shell long ago and it does not take very much time before the shell starts working for you.

Next up, what is that mystique unique to the hacker and their shell?

2.1. Symbol of the Hacker

A blank, black screen and blinking cursor. Lines and lines of scrolling text and someone in front of that screen who seemingly understands an incomprehensible flow of information. That is the shell.

The shell has many other names: the terminal, the command prompt, bash… PowerShell, if you’re looking at Windows and feeling blue. Each name has its own nuances. But that doesn’t matter right now. What matters is that there is the interface to computing devices that nearly all people use, and then there is the shell.

If you’ve come here to get a shell and don’t care for much else, then you should skip to the Get a Shell section. Be warned that the shell is more powerful than the usual way of interacting with a device. Deleting files is permanent in the shell, any file can be accessed at any moment in the shell, and hopefully it’s not farfetched to assert that those two things are a dangerous combination.

2.2. Got Shell?

Using a computer or smart device happens in 1 of 2 ways:

-

Using a pointer such as a mouse, touchpad or finger to select apps, files, or buttons

-

Using keys on a keyboard to enter simple or complex commands (the Shell)

Thankfully, there are TLA’s (Three Letter Acronyms) for both methods described above:

-

GUI. Pronounced "gooey," stands for Graphical User Interface

-

CLI. Sounded out: "See-El-Eye," stands for Command Line Interface

These acronyms are pretty good as far as acronyms go. We will refer to the shell by many names, perhaps sometimes even by the CLI initialism. The GUI doesn’t have as nice of a name as the shell, so we will probably use GUI to briefly refer to the interface that everyone knows about on computing devices that is driven by a pointer on a screen.

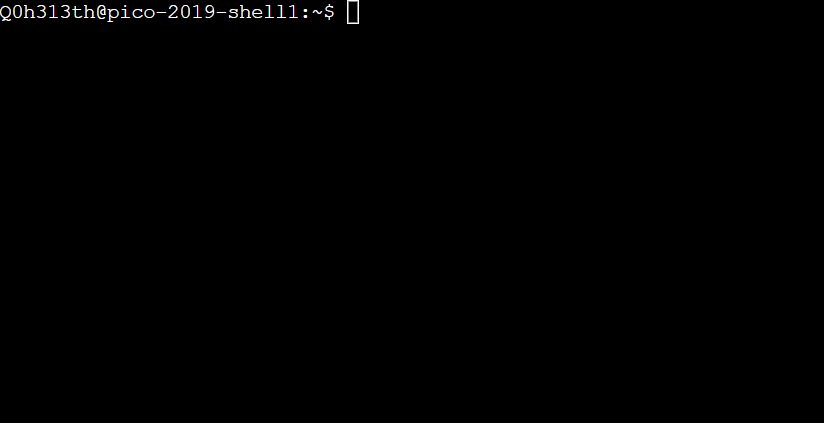

Below is a screenshot of a shell after successful login and before the user has typed in any commands:

In the picture above, there is a lot of empty space, and even the line of text that exists, does not provide a lot of clarity. The situation is simpler than how it looks. There are only 3 pieces of information in the screenshot above, and you would likely recognize at least one of them if it were you who logged on:

From left to right in the shell command line prompt:

-

What does

Q0h313thmean? -

What does

pico-2019-shell1mean? -

What does

~mean? -

What does

$mean?

In terms of raw power, Q0h313th could delete every file they own on this

machine with one command. That’s almost never desirable, and I will wait to

show this command until there is something useful and desirable to do with it.

In terms of useful power, Q0h313th could create a copy of an entire website for

use when there is no accessible WiFi. That’s using the command wget.

Now let’s talk about getting a shell!

2.3. Get a Shell

Cybersecurity is a topic that is most deeply learned by listening and doing. For this reason, I advise you to create a picoCTF account at this point if you have not already. Beyond providing 120+ security challenges in helpful learning ramps, every picoCTF account gets access to a web-based Linux shell.

A note on the structure of my (LT’s) chapters: many times I will provide a high level tutorial for a task and also a step by step walkthrough for the same task. This is my attempt at accommodating different learning styles and, different levels of experience. Typically, the high-level walkthrough is more for learners who already know the basics but need a refresher or need a reminder about the particulars when it comes to this Primer. The step by step walkthrough is more for learners who have never ventured in a particular task before. Of course, you must choose your own path here, but the safest bet may be to read the high-level walkthrough but actually put hands to keyboard for the step by step walkthrough.

2.3.1. High level tutorial

-

Gain access to a practice shell

-

Register for a picoCTF account

-

Click link in email that is sent to registered email address

-

Log in to the picoCTF webshell

-

-

-

2.3.2. Step by Step Walkthrough

Register for a picoCTF account at the link below. You will need to validate the email address you provide by clicking on a link that is sent to it.

After successfully registering, a web shell can be accessed at the URL below. Use the same user name and password that you registered on the picoCTF website to log into the shell at the link below (or in the "Webshell" panel on the picoCTF website) For the sake of security, you will not see your password as you type it in.

2.3.3. Debrief

Congratulations (esp. if this is your first time staring at a command prompt)! The next section focuses on demystifying the shell by relating its usage to devices you’ve probably already used for years; and if not, you’ll join the ranks of those whose first language is Shell.

2.4. GUI-fu to Shell-fu

Our first language as children, whether Spanish, English or anything else primarily for communication with other humans, likely took little conscious effort on our part. For anyone who has learned a second language, it was quite the opposite: very little - if anything - came naturally. Learning Shell for someone who has only "spoken" GUI is like learning a second language. This is good news and bad news. The good news is that Shell and GUI are languages for something you’ve been using for probably years, but the bad news is there is a whole new vocabulary with only a handful of cognates (words that sound and mean the same in both languages) here and there.

The basic computer operations that everyone is familiar with in GUI’s can easily be done in the shell as well. Here’s some of the most common operations for anyone using a computing device:

| Operation | GUI action | Shell action | Shell example | Note |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Start app |

Click or touch icon of app |

Type name of app and press enter |

|

Pressing the Enter key sends the command to the shell to run and return. |

Open file |

Browse to file, click |

Use |

|

|

Download app |

Browse app store, click |

Use |

|

Install ChessX game. The hard part was finding a relevant package name. |

As the table above shows, using a GUI involves browsing and clicking, while using a shell involves knowing a good app to use. Google has made finding the right app for a shell interface much easier than it was years ago. As always for CTF’s, Google is your friend! However, more direct resources can be even more helpful, such as this website below that quickly explains shell commands:

However, things do not always go as planned. The next section deals with those sorts of situations that inevitably arise.

2.5. What the Shell!?

The main severity in the learning curve with the shell is that you must know the apps and commands available to you either by memorization or by looking them up when you need them. Certainly, it is faster to memorize as many as possible.

The other challenge is the amount of typing that sometimes must be done to reference the intended file.

Lastly, interfacing with apps also requires memorizing or looking up names of parameters or arguments.

To summarize, some of the most challenging aspects of using the shell:

-

Memorizing commands (aka apps/programs)

-

Typing out long commands

-

Memorizing arguments for commands

2.5.1. Challenge 1: Memorizing commands

Having a cheat sheet with shell commands listed is a must for overcoming the challenge of memorizing commands. Printing it out is a bonus if possible! (Saves screen space). The cheat sheet linked below is very good!

2.5.2. Challenge 2: Typing out long commands

Many wonderfully brilliant students of mine have not known how to speed up their typing in the shell command prompt until thousands of picoCTF points into their learning. I take responsibility for this, and really, most of us go through that phase, but we do not have to! One word:

TAB

In the shell, pressing the TAB key invokes auto-complete by 1. assuming you’ve spelled the command or file correctly up to the point of pressing tab, and 2. completing the command or file name as much as it can.

The functionality of auto-complete in the shell is so different from auto-complete in other apps, such as those in a phone, that shell auto-complete is often referred to as tab-complete. It takes some practice to get used to, but it is worth the time as it probably cuts number of key presses in half!

Unlike auto-complete for a soft keyboard on a phone, tab-complete is never wrong, however, this is mostly because it makes no guesses and only helps with completing commands and file paths and names. It hardly ever helps complete arguments to commands besides file names. If pressing tab doesn’t do anything, this is either because 1. there is no such command or file name to complete what you’ve already typed into the command prompt, or 2. there are multiple commands or file names that could complete what you’ve already typed into the command prompt. Try typing another letter or two. Hit the tab key again. If nothing more is completed, hit tab one more time. If nothing really happens besides an angry noise or flash, then there is no way to complete what you’ve already typed (maybe there is a typo?), but if the issue is that there are multiple possibilities for tab complete to choose, then these options will display after your second strike on the tab key. The double press of tab can be done at any time, but if there are hundreds of options then the shell will ask for your approval before printing all those options because that’s not usually very helpful.

In the next section, I will guide you through some fundamental shell commands to start getting a sense for the world of the shell.

2.5.3. Shell Nav Exercise 1

# SOME NOTES:

# * text listed after "$" I mean for you to enter into the shell and then

# press enter

# * text listed after "#" are comments from me to you but are ignored by

# the shell

#

# this short tutorial is meant to run through foundational shell commands

# with brief explanations for each

# the following command "parks" your shell in your home directory (which is

# somewhere you can create files!)

$ cd

# the following command shows where your shell is parked

$ pwd

# the following command creates a new directory called "tutorial" where you

# are currently parked

$ mkdir tutorial

# the following command moves your shell and parks it in the "tutorial" folder

# you just created

$ cd tutorial

# pwd stands for "print working directory". "working directory" is the

# technical term for where one's shell is parked

$ pwd

# the following command creates an empty file with the name "note.txt"

$ touch note.txt

# the following command list the contents of your working directory

$ ls

# personally, I prefer a one column output of the contents of my working

# directory, like

$ ls -l

# the following command shows the text content of "note.txt" (which is empty

# right now)

$ cat note.txt

# the following command puts "hello world! I'm a snail" into "note.txt"

$ echo "hello world! I'm a snail" > note.txt

# cat will print something now that there is content in "note.txt"

$ cat note.txt

# the following command makes a copy of "note.txt" called "new-note.txt"

$ cp note.txt new-note.txt

# what is in "new-note.txt"?

$ cat new-note.txt

# * the following command opens "new-note.txt" in a terminal text editor

# * try changing the file, then press Ctrl-X to exit and save

$ nano new-note.txt

# if you were successful, this command should print the new content

$ cat new-note.txt

# if you were not successful, that is just fine. revisit this exercise after

# some more reading and practice!2.5.4. picoGym Problem

Try out your new shell skills with this challenge from the picoGym:

2.6. Conclusion

You may have noticed that we did not cover overcoming challenge 3. If you are

curious, look up the man command explained in this cheat sheet:

Using Google helps with learning commands to help solve problems in the shell, and also the "Explain Shell" website I linked to earlier in this chapter.

3. Forensics

Luke Jones

3.1. What is Forensics?

In general, computer science professionals refer to "Digital Forensics" as "Forensics", for simplicity’s sake. Digital Forensics is the field in cybersecurity that tries to gather and understand evidence after an incident, which can be crime, to determine how it happened. This not only helps law enforcement when pledging someone innocent or guilty, but also to understand how to improve security in a system that was successfully attacked. Digital Forensics focuses on gathering evidence present in computer devices that hold information electronically. It is a branch of Forensic Science, which can also investigate any type of crime even if there is not computer media involved.

3.2. How to search for strings and filenames

We will begin by learning how to search for information in a file system. Go to the picoCTF webshell at:

Once you are connected, open up this problem in a separate tab:

Download the problem file in your webshell by right-clicking the link in the problem description and selecting Copy Address or Copy Link. Then download it by typing in `wget ` and pasting the address after 'wget', space. Your command should look something like this, but is likely to not be exactly the same:

$ wget https://jupiter.challenges.picoctf.org/static/495d43ee4a2b9f345a4307d053b4d88d/fileYou need to copy and paste your own link for the file.

Great! So now you should have the challenge file saved on your webshell as

file. Now what?

As a reflex, you should always use the program file on new files that CTF

challenges give you. The next command is kind of confusing, because the first

word references the program file and the second word references the file

named file, but run this command and see what it tells you:

$ file fileIf done properly, it should tell you:

file: ASCII text, with very long linesThis tells us the file is plain text, but has unusually long lines. Since it

is plain text, we can use cat to see what it contains.

$ cat fileRunning this command will show that the file is mostly made up of gibberish.

If this were a cryptography challenge, decoding the gibberish might be what

needs to happen, but this is a 100 point general skills question, so I doubt

that’s what needs to happen here. What is the challenge author pushing us

towards? There’s only one hint and it is a grep tutorial. What is grep?

Grep is a Linux utility, so we can learn about it by bringing up its man page:

$ man grepThe first line of the man page says:

grep, egrep, fgrep, rgrep - print lines that match patternsThis is perfect! We want to search through gibberish to find the flag. But how do we specify the pattern to search for and the file to search in? For this, I recommend the grep tutorial in the hint, not the man page. (Man pages tend to be highly technical and can be confusing to novices)

One of the first examples in the grep tutorial uses the following command:

$ egrep 'mellon' mysampledata.txt'mellon' is what is being searched for and it is being searched for in 'mysampledata.txt' What if we searched for 'picoCTF' in 'file'? That command would look like:

$ egrep 'picoCTF' fileThis should get the flag for you and print it on your screen.

Let’s consider another challenge:

Download the zip file into your webshell like you did for the previous

challenge. As before, use file on it right away to have an idea of what

you’re dealing with:

$ file files.zipYou should see the following output:

files.zip: Zip archive data, at least v1.0 to extract, compression method=storeTo see more of this challenge, all we have to do is unzip the archive:

$ unzip files.zipYou’ll see a lot of output, but you can ignore that for now. List the contents

of your current directory to see the new directory called 'files'. Try

exploring that a bit with cd and ls, remember that you’re looking for a

file called 'uber-secret.txt'.

It may be hard to find 'uber-secret.txt' without the help of a tool. This problem is called 'First Find' and our last problem was called 'First Grep'. Is there a tool called 'find' in Linux? See if there is a manpage:

man findThere is! The first line reads:

find - search for files in a directory hierarchyThis sounds perfect. Exit the manual by pressing 'q'. As mentioned before,

manpages are quite technical and can be overwhelming to try and read when you

are first starting out. Let’s find some simpler examples by Googling. My

Google query was find file linux command. I felt the need to specify linux

command because find is such a generic word. My top Google result was this:

I especially liked this result because I know plesk is not a commercialized

site. Scroll down to the first example under Basic Examples.

find . -name thisfile.txtThis command means: starting in the current directory (which is what ., dot

means), look in this directory and all subdirectories for the file named

'thisfile.txt'. We can slightly modify this example to fit our needs for the

challenge.

Make sure you are in the 'files' directory for this command. If you unzipped the archive in your home directory, you can use the following command to get back to the 'files' directory:

$ cd ~/filesOnce you’re in the files directory, use this command:

$ find . -name uber-secret.txtIf you were in the 'files' directory when you ran this command, you should get the following output:

./adequate_books/more_books/.secret/deeper_secrets/deepest_secrets/uber-secret.txtThis is the path to the file that was found. We’re going to get into the same directory as this file by following the directories listed in this file path. We know that '.' is our current directory, so our first cd is to 'adequate_books'. Remember to use the Tab key to autocomplete unambiguous file and directory names. To explain what I mean by 'unambiguous' here’s a relevant example of an ambiguous file name in our current context:

$ cd aIf you press the Tab key after only typing 'a' it won’t autocomplete because there are two directories that start with 'a', 'acceptable_books' and 'adequate_books'. The shell doesn’t know which one you want. To get Tab to autocomplete type the following unambiguous directory name and then strike tab:

$ cd adWhen you press tab, it becomes:

$ cd adequate_books/One last note on tab completion. When there is an ambiguous file name that doesn’t tab complete to something, you can hit the tab key again to see the list of files that could be completed with your given prefix. The other possibility is that there are zero matches on your given prefix, in which case nothing is printed when you hit tab a second time.

So now we are in 'adequate_books', what’s next? From our found file above, 'more_books' is after 'adequate_books', so we cd accordingly:

$ cd more_books/For this directory, observe the difference between ls -l and ls -al. You’ll

see that an additional directory is shown when the '-a' flag is given. This

flag means 'show all (including hidden files and directories)'. In Linux, any

file or directory starting with '.' is considered hidden and will only be

shown in specific circumstances.

$ cd .secret/

$ cd deeper_secrets/

$ cd deepest_secrets/All of these cd commands could be combined into a single command, but I’ve broken them up here for clarity and exposition. List the contents of 'deepest_secrets':

$ ls -alTo see the contents of the file, use cat:

$ cat uber-secret.txtThere’s the flag for this challenge!

Try this slightly more difficult challenge with your new found skills:

3.3. Disk analysis

One of the most fundamental skills of a forensics analyst is inspecting and deeply understanding disks. These can be actual hardware or dumps of disks captured in files. There are a few really good GUI tools out there for not just disk analysis, but whole management of digital evidence for cases. Our disk analysis problems will not require any licenses to proprietary software. Some people like to use Autopsy which is a GUI frontend to the tools we will demonstrate how to use in this section. We will use the individual Sleuthkit tools so that you learn a little more than from a GUI that abstracts away some of the details. Disks are all about the details.

3.3.1. Sleuthkit Intro presentation

We will be considering disk images exclusively, due to the difficulty of sending real hard drives through the Internet at the time of this writing! Try this picoGym problem, which presents the first step in analyzing disk images:

This problem should be pretty approachable given what you’ve done leading up

to this point, namely downloading individual challenge files and using command

line utilities. Something new in this challenge is using netcat or nc. For

this challenge, nc is used to access a checker program. This program will check

your answer to the challenge and give you the flag if it is correct. For this

challenge, the invocation of nc (what you type to run it) is given and is

straightforward, but I will explain it for the sake of clarity. Here’s my given

nc invocation: nc saturn.picoctf.net 52279 The last number might be different

for you, that’s expected. We’ll go through what each part of this program call

means:

-

ncThis, of course, is the name of the program we are running. Netcat, or 'nc' as this system calls it. Sometimes the program name will be the full 'netcat' variety, but on the webshell, it is 'nc'. -

saturn.picoctf.netThis is the name of the computer we’re connecting to. This is a challenge server that picoCTF runs. -

52279This is the number of the port we’re connecting to for the challenge. This will probably be different for your challenge.

So go ahead and solve your first Sleuthkit problem on the picoGym and learn the

tool, mmls, which we will use for subsequent problems.

3.3.2. Sleuthkit Apprentice walkthrough

Here’s the next challenge in that short series:

This challenge requires mmls as a first step to use other Sleuthkit tools,

but now is the time for some true forensic background.

A disk image is a huge dump of many numbers. But these numbers have an invisible structure to them that gives them much more meaning. Navigating this invisible structure manually is tedious and deeply difficult, but the Sleuthkit tools handle this invisible structure for us. To begin using the Sleuthkit tools we must understand some of the layers that apply to disk images. The four main layers are: media, block, inode, and filename.

-

Media: the media layer tools all are prepended with 'mm' and operate on the disk image with little guidance from the analyst.

mmlsis a media layer tool that gives us the partition table of the image and key information for delving into the other layers. Media is the lowest level, providing key information to access the deeper layers, but not shedding much light on the data contained in the image. -

Block: the block layer is the second lowest level of the four layers considered here. Block layer tools are prepended with 'blk' in the Sleuthkit.

blkcatis a block layer tool that outputs the contents of a single block. The block layer is the numbers of the disk image broken into equal-sized chunks. A single file is likely to contain multiple blocks. -

Inode: the inode layer is the bookkeeping layer of a disk image. It’s like the table of contents, with the chapter numbers being like the inodes, and the pages like the blocks of a file. Inode layer tools are prepended with 'i'.

icatis an inode layer tool that outputs a single file based on its inode number. -

Filename: the filename layer is one layer that most any user of a computer actually sees and interacts with. This is the layer with which we will start our exploration of the Sleuthkit in the current challenge. Interacting with the filename layer will look a lot like using the shell normally. Filename layer tools are prepended by 'f'.

flslists the files on an image starting at the root. This is what we will use for our exploration of the disk image.

First off, download the challenge file:

$ wget https://artifacts.picoctf.net/c/331/disk.flag.img.gzNext, decompress the challenge file:

$ gunzip disk.flag.img.gzDump the partition table of the disk image. We want to find the offset to the main partition:

$ mmls disk.flag.img

DOS Partition Table

Offset Sector: 0

Units are in 512-byte sectors

Slot Start End Length Description

000: Meta 0000000000 0000000000 0000000001 Primary Table (#0)

001: ------- 0000000000 0000002047 0000002048 Unallocated

002: 000:000 0000002048 0000206847 0000204800 Linux (0x83)

003: 000:001 0000206848 0000360447 0000153600 Linux Swap / Solaris x86 (0x82)

004: 000:002 0000360448 0000614399 0000253952 Linux (0x83)It would seem that the fourth partition is the main partition, because it is

the largest and has an uneven length. That’s a bit of a guess, but it’s for

sure either partition labeled 'Linux (0x83)'. Copy the 'Start' value to your

clipboard of the fourth partition. Let’s look at the root of this partition by

supplying the 'Start' value to the offset option in fls:

$ fls -o 360448 disk.flag.img

d/d 11: lost+found

d/d 12: boot

d/d 1985: etc

d/d 1986: proc

d/d 1987: dev

d/d 1988: tmp

d/d 1989: lib

d/d 1990: var

d/d 3969: usr

d/d 3970: bin

d/d 1991: sbin

d/d 451: home

d/d 1992: media

d/d 1993: mnt

d/d 1994: opt

d/d 1995: root

d/d 1996: run

d/d 1997: srv

d/d 1998: sys

d/d 2358: swap

V/V 31745: $OrphanFilesThis looks like the main partition because it has many of the standard linux

root directories, like 'home', 'usr', 'root', etc. Remember that fls is part

of the filename layer Sleuthkit tools. You can think of fls as standing for

'filename list'. Here, it’s listed all the top-level directories in the disk

image.

This next part requires some forensic intuition. A lot of these directories

are system-generated and maintained. Let’s focus on the directories that have

a lot of potential user influence like root and home. But first, let’s

take a step back and print the help information for fls:

$ flsfls will print some succinct help information if ran with no arguments. This

is true for many command line tools and programs, but is not universal.

$ fls

Missing image name

usage: fls [-adDFlhpruvV] [-f fstype] [-i imgtype] [-b dev_sector_size] [-m dir/] [-o imgoffset] [-z ZONE] [-s seconds] image [images] [inode]

If [inode] is not given, the root directory is used

-a: Display "." and ".." entries

-d: Display deleted entries only

-D: Display only directories

-F: Display only files

-l: Display long version (like ls -l)

-i imgtype: Format of image file (use '-i list' for supported types)

-b dev_sector_size: The size (in bytes) of the device sectors

-f fstype: File system type (use '-f list' for supported types)

-m: Display output in mactime input format with

dir/ as the actual mount point of the image

-h: Include MD5 checksum hash in mactime output

-o imgoffset: Offset into image file (in sectors)

-p: Display full path for each file

-r: Recurse on directory entries

-u: Display undeleted entries only

-v: verbose output to stderr

-V: Print version

-z: Time zone of original machine (i.e. EST5EDT or GMT) (only useful with -l)

-s seconds: Time skew of original machine (in seconds) (only useful with -l & -m)The first line after our fls invocation with no arguments is an error

message, saying that we failed to include a mandatory argument, the image

name. However, fls uses the opportunity to educate us on how to properly

invoke it. All arguments in square brackets, i.e. '[' and ']', are optional.

Anything not in square brackets is mandatory. After the invocation is a

helpful note saying 'If [inode] is not given, the root directory is used'.

This is how we first used fls. We supplied no inode and the root directory

was printed. But now, we want to look at specific directories so we will need

their inodes. Helpfully, fls actually prints those along with file and

directory names. It’s the number on the line with each name, if we look back

to our listing of '$ fls -o 360448 disk.flag.img' we can find the inode number

for /home which is 451. Let’s add that to our fls call:

$ fls -o 360448 disk.flag.img 451

$This actually seems to do nothing. It’s not actually doing nothing, there just

are no results. /home is an empty folder in the disk image. Let’s try

another directory, /root. Go back and get the inode number and plug it into

fls:

$ fls -o 360448 disk.flag.img 1995

r/r 2363: .ash_history

d/d 3981: my_folderThis directory has a file, called .ash_history and a directory named

my_folder. Let’s see what is in 'my_folder'. Use the inode number like

before:

$ fls -o 360448 disk.flag.img 3981

r/r * 2082(realloc): flag.txt

r/r 2371: flag.uni.txtBingo! Now with the inode number of 'flag.uni.txt' we can print the file using

icat:

$ icat -o 360448 disk.flag.img 2371

picoCTF{by73_5urf3r_adac6cb4}Please be aware that your flag will likely have a different suffix.

Now, it’s good to go back and address what the other file in 'my_folder' was.

Its name is flag.txt, why can’t we icat that file? In short, because the

file has been deleted and the inode has even been reassigned to a different

file. You can try using icat on the 2082 inode, but it is part of an

unrelated file somewhere on the system.

If you want to continue to learn about Sleuthkit tools, try this problem:

If you want to use what you know to dive even deeper into a disk, try this problem:

If you get stuck, try reading writeups of the challenges. Just google search 'Writeup, [challenge name], picoCTF'. There’s going to be various levels of quality and depth in writeups, so don’t feel like you have to stick with the first one you look at.

3.4. Packet analysis

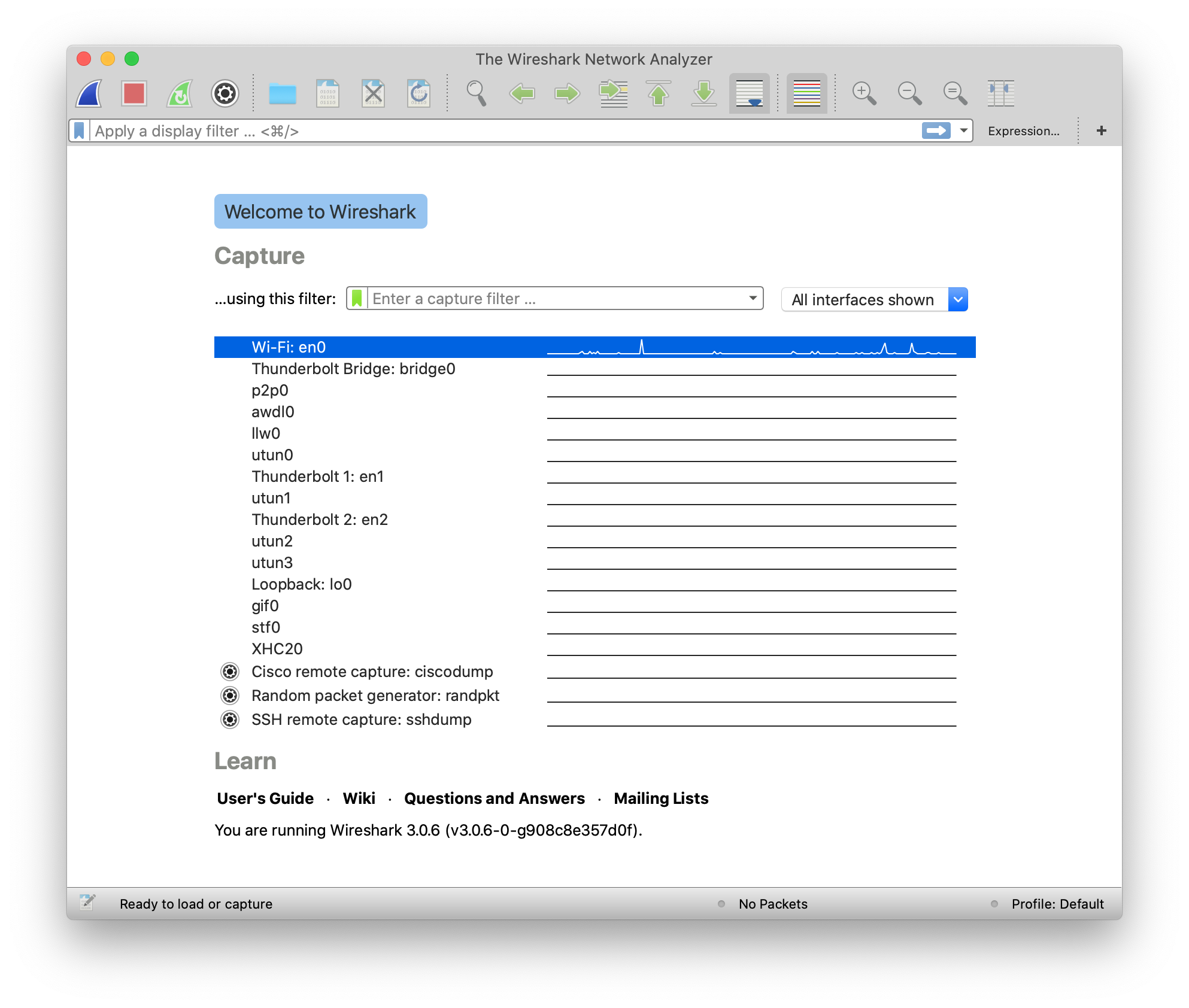

Another important field of forensics is packet or network analysis. This field of forensics conerns itself with understanding what has happened on a network through the examination of captured packets. This will require the use of a GUI tool called 'Wireshark', which means you cannot use the webshell to complete this problem. The webshell can be used to complete many introductory problems, but more advanced problems sometimes need a GUI tool to be solved in an efficient manner. Consider this an exercise in installing and using GUI tools. Knowing how to do this will help you greatly in the future.

3.4.1. Installing Wireshark

On your computer, download Wireshark from their site:

You must download the version corresponding to your operating system. It should be a straightforward process, however, if you have any issue or doubt, you can Google plenty of good documentation about Wireshark.

If you’re using a Chromebook you will need administrator privileges to enable Linux mode on the device. With Linux mode enabled, you can install Wireshark through apt-get and run it with the Linux terminal.

3.4.2. Packet Primer walkthrough

Consider this picoCTF challenge:

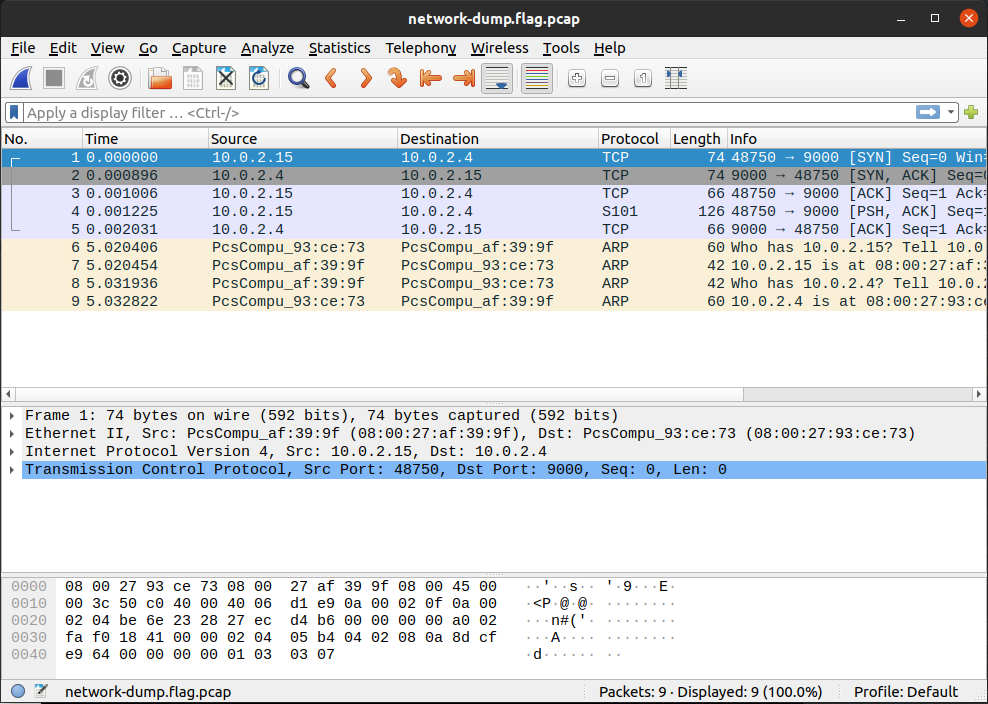

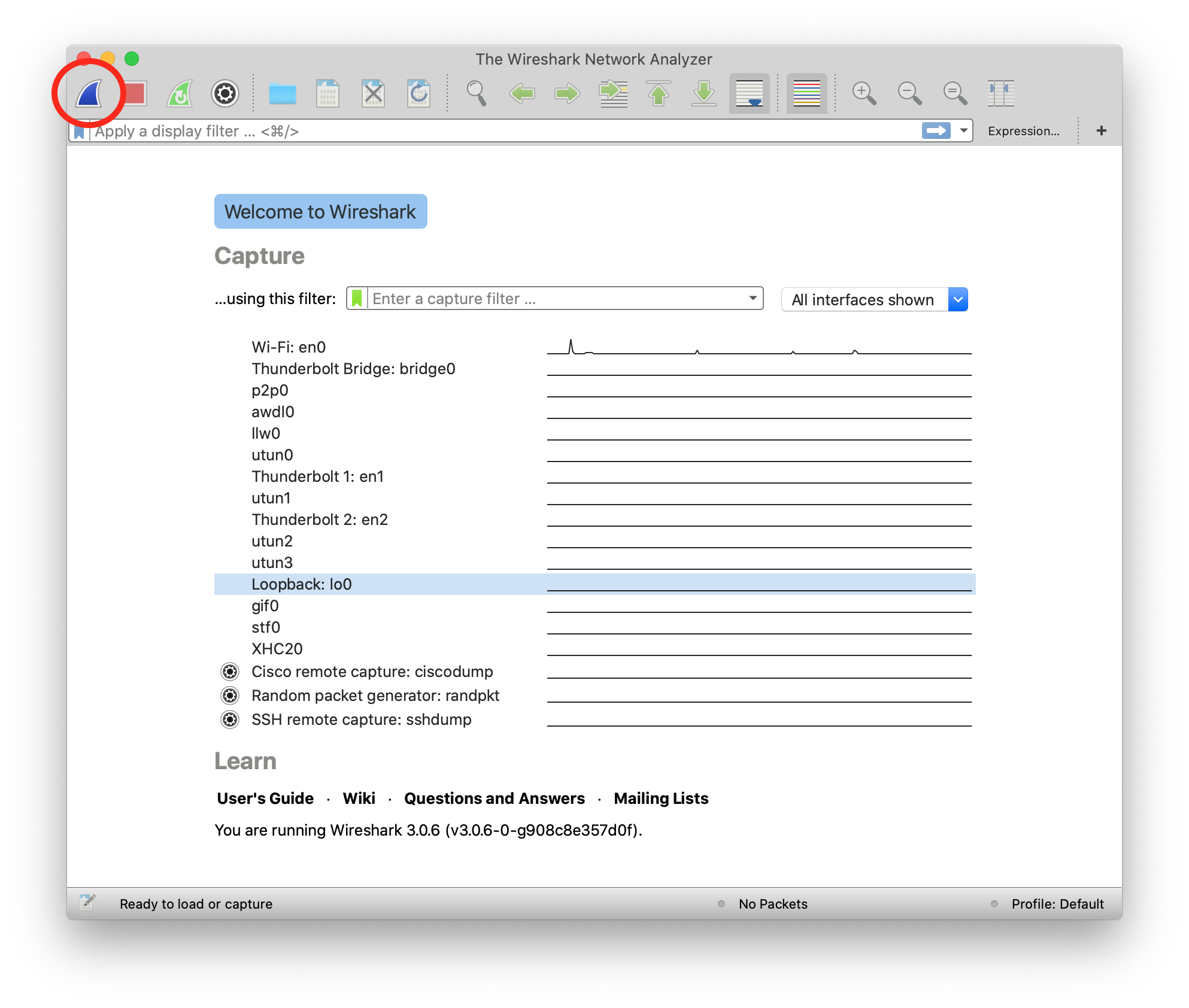

Download the packet capture and open it in Wireshark. It should look like this once you open it. Google how to open a packet capture in Wireshark if you can’t figure it out by exploring the menus of the tool.

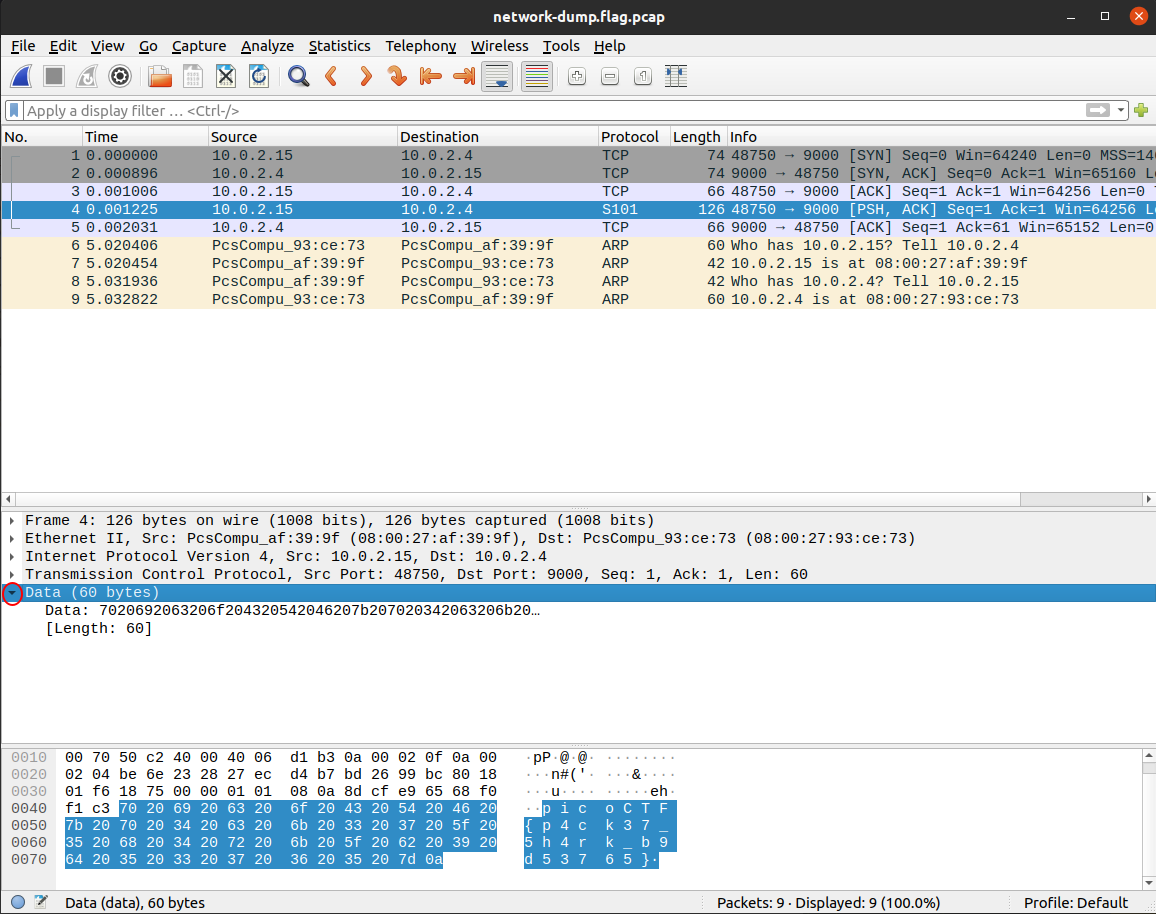

Packet analysis is all about filtering, even for this packet capture that is tiny. Most packet captures are going to have thousands if not tens of thousands of packets. This capture has only 9 because it is an introductory problem. You could manually inspect each packet and that wouldn’t be a bad strategy, but we want to approach this problem more technically, because it is just setting us up for future problems that have thousands of packets.

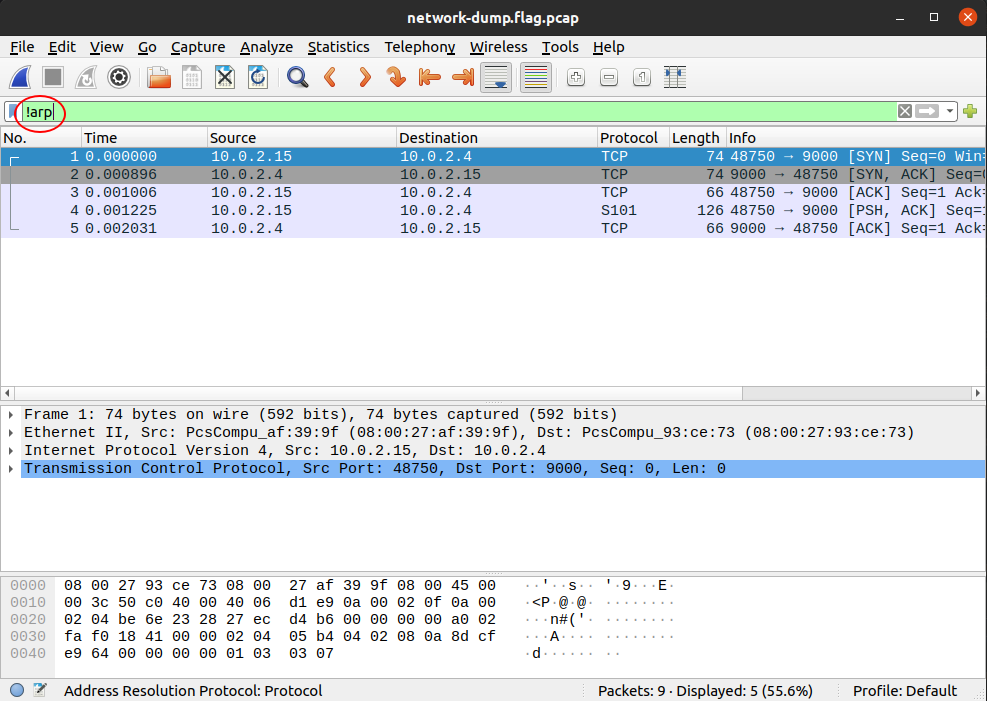

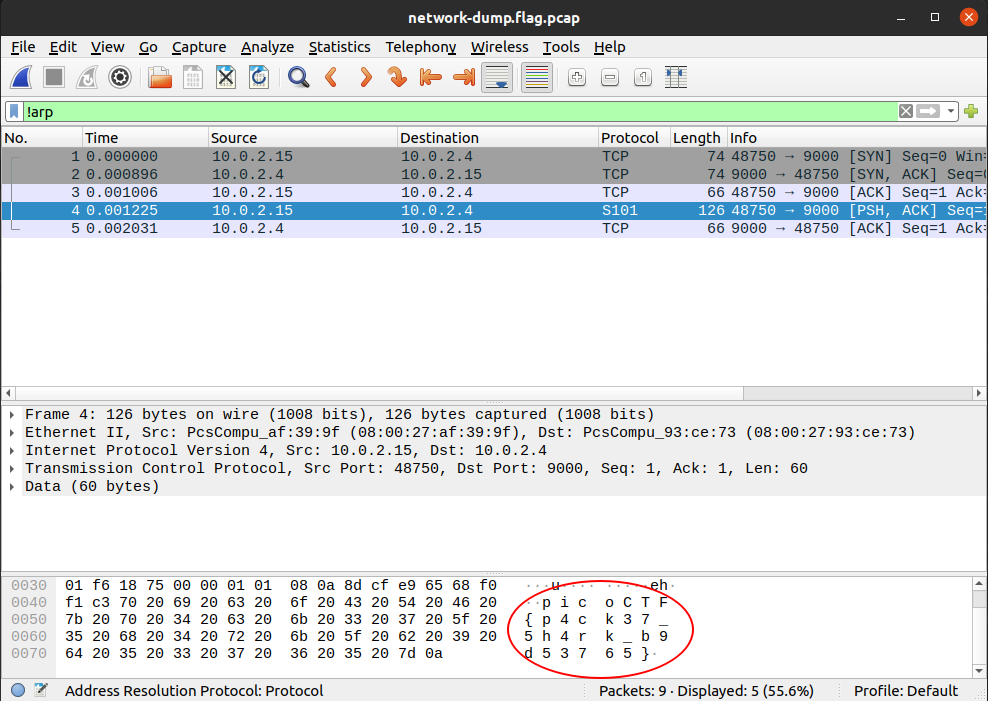

So, we know that the flag is unlikely to be in the ARP messages as these are

just messages relating IP addresses and hardware addresses. To filter out ARP

messages, add !arp to your filter in Wireshark:

| 'ARP' stands for Address Resolution Protocol and these messages are common in every network capture as it is needed to connect a hardware address to an IP address. |

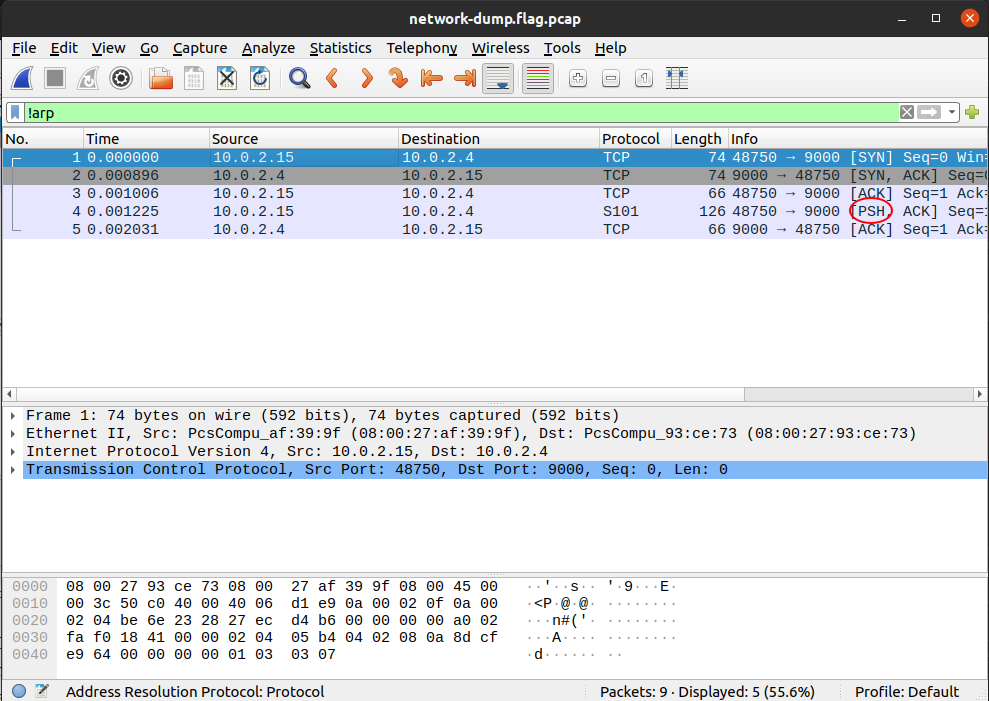

Of the remaining 5 packets, the first 3 are the TCP handshake and so they can be ignored. Of the remaining 2 packets, let’s look at the one that has the PSH flag set, which means there is data for the application in the packet:

| The TCP handshake, also known as the 'three-way handshake' can be identified by the flags in the packets. First 'SYN' from host A, the 'SYN, ACK' from host B, then finally, 'ACK' from host A. 'SYN' stands for synchronization, and 'ACK' stands for acknowledgement. Both parties synchronize and acknowledge. |

When you click on packet 4, you should see the flag in the packet bytes pane, you may have to scroll down to see it all:

Remember, your flag might be different than mine. It would be good to notice that there was something different about the packet with the flag from the beginning. It has a protocol of 'S101', and it’s the only one. Such glaring oddities should always be examined. Sometimes, the only clue in a packet analysis problem is a small difference between the flag packet and the rest of the thousands of packets. A good strategy is to filter as many packets as you can, then look for oddities. I should note also that there is not always a 'flag packet'. Sometimes a flag can span across multiple packets, just like packet payloads can span across multiple packets.

| 'S101' is an uncommon protocol. The packet isn’t really speaking S101, it is just using the preferred port of the protocol, port 9000. |

Leave your packet capture open if you can. We are going to use it to illustrate concepts introduced in the next section.

3.4.3. Network Layers

We’ll now cover some background to deepen your understanding of packets and networks. The networks we commonly use today, are broken down into different layers. This design by layers assigns responsibilities to each layer to accomplish something. It is good to have a design by layers for several reasons. For example, if network engineers want to make a change in one of the layers, the impact on the other layers is minimized. Another example, is that if you are a programmer and want to connect your application with a server, you do not necessarily need to care if the user is using wifi or ethernet cable, or how the user is connecting to the internet. Your application can simply trust other layers are going to take care of that and your application will have a successful connection. These are the layers, viewed in a top down approach.

-

Application layer: Responsible for handling data traffic between applications. HTTP belongs to this layer; HTTP protocol is commonly used to obtain Web Pages. In the Packets Primer capture, click the fourth packet. This packet’s application layer is called 'Data' in the middle pane. Click the arrow to expand the view of the layer. There’s not much in this display because the application data is just the flag. Other layers will break down all the fields of a layer, showing the value for each one in the packet.

Figure 6. Application layer expanded

Figure 6. Application layer expanded -

Transport layer: Responsible for providing several connections on the same host, that means that you can have several applications on the same device and each of them can have a different connection even if it is just one device. It also defines functionalities for reliable transport. Two protocols are used on this layer. TCP (Transport Control Protocol). You use this protocol when you need to have reliable transport, this makes sure that if a piece of information was missing while being transfertransferred it is resent. HTTP from the Application layer, runs on top of TCP, because when you visit a Web Page you want to have every part of it accurately. On the other hand, when you don’t need reliable transport, but you want faster transport that does not resend parts that were missing, UDP (User Datagram Protocol) is used. An example when UDP is needed is for voice communication. When you are talking if a little part of the audio is missing, you do not want it to appear later in the communication because that would confuse the listener. The listener can still understand what you are saying if the part missing is small enough. Since UDP has no controls for transport, it is faster than TCP. This layer assigns a port to each connection, and that is how it tells the difference between connections in the same computer, because of the port.

-

Network layer: It provides devices with an address in the network called the IP (Internet Protocol) address, and routes information through different routers. It provides mapping between all the computers connected to the internet. When you connect to a network in some specific place, an IP is assigned to your device.

-

Data link layer: It provides communication between devices that are connected directly. Examples of protocols in the data link layer are Ethernet or WiFi. You generally use WiFi to send messages to your router directly without any other devices in between. Each device has a physical address in wifi or ethernet, known as the mac address. The mac address is used for this layer. This is not an address like the IP that can change depending on the network you are connected to. The mac address is assigned to the hardware of your network card when it is manufactured.

-

Physical layer: This handles electrical pulses on the wire that represent bits.

4. Programming in python

Samuel Sabogal Pardo

A computer program is a set of instructions that allow us to do a task automatically on a computer. We can make a computer program in a programming language. Computer programs are generally called "software". With a computer program we can do all sorts of things. Some examples are calculators, video games, text processors, browsers, and all the things you have ever used in a computer. Nowadays, there are computers everywhere. Any device such as a cell phone, smart watch, or modern car is running software that was made in programming. To begin, we are going to learn python, which is one of the easiest programming languages to learn.

Let’s begin writing python! We are not going to explain each detail of python independently. For that, you could read the python documentation, which is located here:

However, if you don’t know any programming, going directly to the documentation can be overwhelming. We are just going to explain some parts of python which are a good start to begin to write your own programs to exploit software. We do this by making examples that achieve one objective and we explain how they work along the way. This will allow you to read code written by someone else, of course, with the help of google if they use elements that you did not know previously.

When you are learning a programming language, there is a tradition in which the first program you write simply prints "Hello World!"" on the screen. We will be using python 3, the number 3 is the version of python. Let’s start doing the "hello world!" program.

Open your shell, go to your home directory, and create a folder called "python_examples". You can do it with the following lines:

$ cd

$ mkdir python_examplesNow, access that folder using

$ cd python_examplesCreate a file called "helloworld.py", you can do it with:

$ nano helloworld.pyTo make our 'hello world!' program in python requires just one line of code! Simply write this on the file:

print("Hello World!")Now save the file in nano by pressing 'control' and 'x' at the same time, and then press 'y', then 'enter'.

Run the program on the terminal with:

$ python3 helloworld.pyYou should see that "Hello World!" is printed on the screen when you run it:

$ python3 helloworld.py

Hello World!That was our first program in python!

Python, as any other programming language, has variables. A variable can hold different types of data. What we just printed on the screen was a string of characters. When we enclose something in quotes, we are telling python it is a string of characters. A string is a data type. In python, to create a variable we simply choose a name and assign the value that we want. For example, we are going to create a variable called my_string, and we are going to assign to that variable the value "Hello World!":

my_string = "Hello World!"That line of code makes the variable my_string equal to "Hello World!". In python programming, the symbol = is used to assign the value from the right side of the equal to the variable at the left side. Variables can have any name we like, except some specific words that are reserved for python instructions. For example, the word 'print' is reserved, so you cannot use it as a variable name.

Now, if we print the variable, it should print "Hello World!". Do that experiment next. The python script should look like this:

my_string = "Hello World!"

print(my_string)Run it and you will see "Hello World!"" printed on the screen again.

Hello World!You can also assign numbers to variables and do mathematical operations between them. Let’s make a simple program that calculates the area of a square. Create a file called "area.py" and write the following:

side1 = 4

side2 = 8

result = side1 * side2

print(result)If you run that script, what do you think is going to print?

When you run it you should see:

32Those were very trivial examples. Now, suppose you want to print a list of 20 numbers that starts at 0 and ends at 19. We can do that in just a couple of lines, instead of writing 20 prints! Create a file called loop.py and use the following code:

for i in range(20):

print(i)Run it and you should see:

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19We have introduced the concept of a python loop. The word 'for' is used to declare a 'for loop', which is a loop that iterates in a range of numbers. The 'i' next to 'for', is a variable that will be incremented on each iteration on a range of 20. We can change the range for a bigger one or a smaller one by changing the number inside the parenthesis. Note that a line of code will be inside the loop, if it is indented by four spaces. For example, run this:

for i in range(10):

print("I am inside the loop")

print(i)

print("I am OUTSIDE")You will see:

I am inside the loop

0

I am inside the loop

1

I am inside the loop

2

I am inside the loop

3

I am inside the loop

4

I am inside the loop

5

I am inside the loop

6

I am inside the loop

7

I am inside the loop

8

I am inside the loop

9

I am OUTSIDENote that the string "I am OUTSIDE" was printed only once, because it is outside the loop. To be inside the loop the code needs to be indented by 4 spaces, as we said. Once we use a line of code that is not indented for the first time after the loop, that is considered the end of the loop. If you try to indent a line after the loop has finished, like this:

for i in range(20):

print("I am inside the loop")

print(i)

print("I am outside")

print("I am outside 2")That would cause a syntax error when you run it. A syntax error means that the code is not complying with the way python should be written. In this case, would specifically show an indentation error:

python3 helloworld.py

File "helloworld.py", line 5

print("I am outside 2")

^

IndentationError: unexpected indentThat happens because we put an indentation, and the for loop was already closed. Syntax errors at the beginning can happen to you by accident and you might not fix them very easily, but with a little time you will begin to fix them quickly if they happen. To practice, spot the syntax error in the following code:

for i in range(20):

prin("I am inside the loop")

print(i)

print("I am outside")What is the error?

Run it to see what happens. It will show:

python3 helloworld.py

File "helloworld.py", line 2

prin("I am inside the loop")

^

SyntaxError: invalid syntaxPython shows you the line with the error, but not the exact location. In this case we missed the 't' from 'print'. Another error might be that the colon from the for loop is missing:

for i in range(20)

print("I am inside the loop")

print(i)

print("I am outside")In that case it will show you:

python3 helloworld.py

File "helloworld.py", line 1

for i in range(20)

^

SyntaxError: invalid syntaxIf you add the missing colon after range(20), the program should work. A syntax error can happen because any reserved word is misspelled; remember that reserved words are words that python recognize as instructions. For example, 'print', 'for', 'in' are reserved words in our program. Additionally, a syntax error can happen because of a missing symbol such as a colon.

As a challenge, implement a program that prints your name 10 times, and below your name prints a number starting at 100 and ends at 109. The output of your program should look similar to:

Samuel

100

Samuel

101

Samuel

102

Samuel

103

Samuel

104

Samuel

105

Samuel

106

Samuel

107

Samuel

108

Samuel

109Hint: use range(100, 110).

Once you are done with the previous challenge, fix the following program that has several syntax errors and make it work:

for i inn range(10:

prnt(i)The program should print the numbers from 0 to 9.

So far, we have seen how a computer can repeat an instruction several times, which is something fundamental in a computer. We want computers to do repetitive tasks for us. Another fundamental functionality we want in computers is conditional clauses. A conditional clause means that a program will do an action only if a condition is met or take another path if the condition is not met. For example, suppose you are printing the numbers from 0 to 9, and you want to print a message when the number is less than 5 and another message when the number is equal or greater than 5. You would do it in the following manner:

for i in range(10):

if i < 5:

print("The following number is less than 5")

if i >= 5:

print("The following number is greater than or equal to 5")

print(i)Run it and verify the results. We have introduced an if-clause, which is a conditional clause. Note that all the code is inside the loop. The first message is inside the first if-clause, that is only fulfilled when 'i' is less than 5. The second message is inside the second if-clause, which is only fulfilled when the 'i' is greater than or equal to 5. At last, we print the variable 'i', which is not inside any if-clause, so it is always printed.

Another way to implement this program, is using an 'else':

for i in range(10):

if i < 5:

print("The following number is less than 5")

else:

print("The following number is greater than or equal to 5")

print(i)When then condition in an if-clause is not met, it enters the 'else' to execute what is inside. You should still see this output when you run the program:

$ python3 helloworld.py

The following number is less than 5

0

The following number is less than 5

1

The following number is less than 5

2

The following number is less than 5

3

The following number is less than 5

4

The following number is greater than or equal to 5

5

The following number is greater than or equal to 5

6

The following number is greater than or equal to 5

7

The following number is greater than or equal to 5

8

The following number is greater than or equal to 5

9To practice, implement a program that prints a range of 100 numbers and prints a different message when the numbers are smaller than 10, another message when the numbers are between 10 and 50, and another message when the numbers are greater than 50.

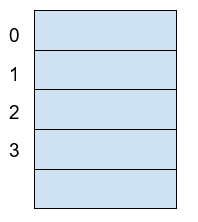

4.1. Lists

There are several data structures in python, which are simply structures to organize data in a certain manner. Different data structures have different properties. We are going to introduce one that is called a 'list', which allows us to store several values, one after the other.

We create a list like this:

my_list = ["I", "Love", "picoCTF"]

print(my_list)We can iterate in the list to operate on each item in any way we want. For example, suppose we want to print each item of the list, we could do this:

my_list = ["I", "Love", "picoCTF"]

print(len(my_list))

print(my_list)

for i in my_list:

print(i)When you run that program, you should see the following output:

3

['I', 'Love', 'picoCTF']

I

Love

picoCTFNote that the number 3 printed is the length of the list. You can sort the list alphabetically by calling a function that is part of the list like this:

my_list = ["this", "is", "not", "ordered", "alphabetically"]

my_ordered_list = my_list.sort()

for i in my_list:

print(i)You should see this output when you run that program:

alphabetically

is

not

ordered

thisNow, create a list of numbers, and print it backwards! Using google, it should be very easy to find how to do it.

4.2. Functions

If you have a piece of code that you want to use often, copy pasting that piece of code is a bad idea because your code gets longer and for a human becomes harder to read. On the other hand, if you want to make a modification in that piece of code, you will have to modify every part in which you copy and pasted that code. We can overcome that by using functions. A function can receive parameters, which are variables you pass to the function so operations with them can be done. Additionally, a function can return a value, which is the result after all the operations are done. Let’s see an example of a function that verifies if a number is even or odd. If it is even, it will return True. If it is odd, it will return False. The program receives any number you input and verifies such an input. Note that the '%' operator in the code is the modulo operator, which calculates the remainder. In this case we calculate the remainder of x divided by 2 and compare that to zero to determine if the number is even or odd. Read the code to understand!

def even_odd(x):

if (x % 2 == 0):

return True

else:

return False

print("Input a number:")

my_number = int(input())

if even_odd(my_number):

print("The number is even")

else:

print("The number is odd")Run that program and try several numbers!

4.3. Input and output

A program might need to have interactions with a user. For example, a calculator expects that the user enters some numbers to then do the processing. Receiving user input in a terminal is very easy in python because it has predefined functions that do it for us. The function ‘input()’ waits until the user writes something in the terminal and presses enter. Note that a function can have zero parameters. Then, the function returns the string that the user wrote, and we assign it to the variable number_iterations’. Here is an example, in which we allow the user to control the number of iterations of our program:

print("Input the number of iterations:")

number_iterations = int(input())

for i in range(number_iterations):

if i < 5:

print("The following number is less than 5")

else:

print("The following number is greater than or equal to 5")

print(i)Run that program. When you run it, it will do nothing until you input a number in the terminal and press enter.

In other cases, the data we want to input does not have to come from the user. It could come from a file. We can read all the lines from a file using the function 'open'. Create a file called “pico.txt” in the same folder that you are creating the python programs. Then, in that file copy and paste this text:

The Cosmos is all that is or was or ever will be.

Our feeblest contemplations of the Cosmos stir us

-- there is a tingling in the spine,

a catch in the voice,

a faint sensation,

as if a distant memory,

of falling from a great height.

We know we are approaching the greatest of mysteries.Save the file. Now, in the same folder, create a program with the following code:

filepath = "pico.txt"

i = 1

with open(filepath, "r") as my_file:

for line in my_file:

print(i)

print(line)

i += 1You should see the following output when you run the program:

1

The Cosmos is all that is or was or ever will be.

2

Our feeblest contemplations of the Cosmos stir us

3

-- there is a tingling in the spine,

4

a catch in the voice,

5

a faint sensation,

6

as if a distant memory,

7

of falling from a great height.

8

We know we are approaching the greatest of mysteries.As you saw, this program reads a file and enumerates each line in the output. The 'open' function has two parameters, the first one is the path of the file you want to open, and the second has a string with the letter 'r', which means that we want to read the file. 'my_file' is just the name of the file we want to read. Then, we can iterate over each of the lines of the file in a for loop.

Note that this is all made inside a 'with' block. We use the 'with' statement before opening a file to close the file automatically after reading. Also, to handle possible exceptions during the execution. What that means is that when you open a file, you must close it and make sure that it closes correctly. For example, if you do my_file.close(), that would close the file. Imagine that along the way before calling close, something happens and you never get to the line in which you close the file, so you left it open accidentally. Later we will give you more details on exceptions. For the time being, just think of 'with' as an easy way to ensure that the file will be closed correctly.

If you want to save your output in another file, you can easily do it in the following manner:

filepath_read = "pico.txt"

filepath_write = "outputpico.txt"

i = 1

with open(filepath_read, "r") as file_read:

with open(filepath_write, "w") as file_write:

for line in file_read:

file_write.write(str(i) + "\n")

file_write.write(line + "\n")

i += 1

print("look inside your folder...")We introduced some new concepts in this code. This:

str(i)Is a cast from an integer to string. We want to convert that integer into a string to be able to concatenate two strings. For example, if we have the string "hello" and the integer 123, and we want to create a string that is "hello123", we can concatenate those two values. But first, we need to convert the integer to string, otherwise python will show an error. To concatenate strings, we use the operator '+'. When we add two strings, python will concatenate them. When we add two integers, python will do a mathematical addition. To represent a break of line in a string, we use "\n".

After this explanation, you should know that this:

str(i) + "\n"Simply converts an integer to string, and then we concatenate a break line to it. We do that, because the function line write() does not add a breakline to the string after it writes it, so we would have a file with a single huge line of text if we don’t do that. When you run the code, you should see no output in the terminal, but if you show the contents of the folder you are in, you should see a new file called 'outputpico.txt'. If you show the contents of that file, you should see the following:

$ cat outputpico.txt

1

The Cosmos is all that is or was or ever will be.

2

Our feeblest contemplations of the Cosmos stir us

3

-- there is a tingling in the spine,

4

a catch in the voice,

5

a faint sensation,

6

as if a distant memory,

7

of falling from a great height.

8

We know we are approaching the greatest of mysteries.We just learned how to read and create files!

4.4. Comments

It is a good practice to explain what your code is doing in a comment. In that way, the reader of the code, which may be yourself, will understand what some part of the code is doing. You will realize that when you write some code, you will forget the exact logic and you will have to read it again to understand what you did. In summary, comments are something very important in programming. In python, you write a comment by adding the '#' symbol at the beginning of any line of your code. This line, will be ignored by the python interpreter as it did not exist, so it does nothing in the program. See the following example:

print("Input the number of iterations")

# We read user input and assign it to the variable number_iterations

number_iterations = int(input())

# We iterate according to the value input by the user

for i in range(number_iterations):

if i < 5:

# We only print this message when the value of i is less than 5

print("The following number is less than 5")

else:

# We only print the value of i is greater than or equal to 5

print("The following number is greater than or equal to 5")

# We always print this

print(i)4.5. Try-except and exceptions

Exceptions are useful in hacking in several cases, for example, when you want an attack to keep executing even if an unknown error occurred. When a program tries to execute an instruction that even though it has a correct syntax, it cannot be done for some other reason, an exception is thrown. For example, if you try to divide a number by zero, that can have the correct syntax to do it, but when the program is executing the line it will stop and fail. Let’s do the experiment:

num1 = 8

print("Input the number that will divide:")

num2 = int(input())

result = num1 / num2

print(result)

print("The program keeps executing to do other stuff...")As you can see the program divides 8 by any number input by the user. If you run it and input for example 2, nothing bad will happen, and you will see this:

Input the number that will divide:

2

4

The program keeps executing to do other stuff...Now, run the program again and input 0, you will see this:

Input the number that will divide:

0

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "helloworld.py", line 4, in <module>

result = num1 / num2

ZeroDivisionError: integer division or modulo by zeroAn error ocurred because you cannot divide by zero. That is a rule of python and most programming languages. Your program will stop when an error happens, further lines will not be executed. In this case, you could verify that the number is not zero in an if-clause. For this example, let’s fix the program instead using a try-except:

num1 = 8

print("Input the number that will divide:")

num2 = int(input())

try:

result = num1 / num2

print(result)

except:

print("An error has occurred, did you try to divide by zero?")

print("The program keeps executing to do other stuff...")In our previous code, you would print the same message for any error. Try to input a string instead of 0. It will show the same message. If you want to be more specific, you can catch specific errors in the following manner:

num1 = 8

print("Input the number that will divide:")

try:

num2 = int(input())

result = num1 / num2

print(result)

except ZeroDivisionError:

print("Do not divide by zero, that is forbidden.")

except ValueError:

print("Your input value must be an integer.")

print("The program keeps executing to do other stuff...")Now when you input a string, it will show this:

Input the number that will divide:

"Any string"

Your input value must be an integer.

The program keeps executing to do other stuff...And if you input zero it will show this:

Input the number that will divide:

0

Do not divide by zero, that is forbidden.

The program keeps executing to do other stuff...Note that when an error occurs, the following lines inside the 'try' block will not execute. See that 'result' is not printed, and that makes sense because there was no result to print. The program jumps into the ‘except’ block immediately.

4.6. Pass arguments to a python program

When you call a program from the command line, it is possible to pass arguments in the same way you do with several programs in the terminal. The following program shows how to do this:

import sys

print('Number of arguments:', len(sys.argv), 'arguments.')

print('Argument List:', str(sys.argv))

# The number of iterations is taken from the second argument.

# (Remember that in an array [0] is the first one, [1] is the second one.)

number_iterations = sys.argv[1]

f = open("output2.txt", "w")

for i in range(int(number_iterations)):

if i < 5:

f.write("The following number is less than 5\n")

else:

f.write("The following number is greater than or equal to 5\n")

f.write(str(i)+"\n")

f.close()

print("look inside your folder...")Put this code into a file called "args.py". If you run it without any arguments, it will throw an error:

$ python3 args.py

Number of arguments: 1 arguments.

Argument List: ['args.py']

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "args.py", line 8, in <module>

number_iterations = sys.argv[1]

IndexError: list index out of rangeThis error happened because the program is expecting an argument on the command

line, but none is given. More specifically, the second argument in the argument

list is queried sys.argv[1] but it doesn’t exist! Do take note, however, that

even without supplying any arguments to the program, the program name is

considered the first argument. To run this program properly, we must include an

integer argument to our program call:

$ python3 args.py 6

Number of arguments: 2 arguments.

Argument List: ['args.py', '6']

look inside your folder...

$ cat output2.txt

The following number is less than 5

0

The following number is less than 5

1

The following number is less than 5

2

The following number is less than 5

3

The following number is less than 5

4

The following number is greater than or equal to 5

5Take note that since we did not use with to open our file, we had to close it

manually with the line:

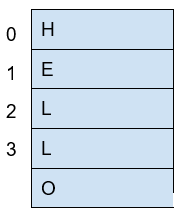

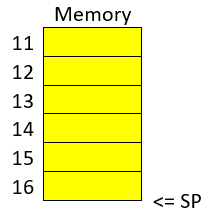

f.close()4.7. ASCII

ASCII is a way in which a computer represents characters. We could say that in memory a computer only stores numbers, but a program can interpret those numbers in a certain way to understand them as characters.

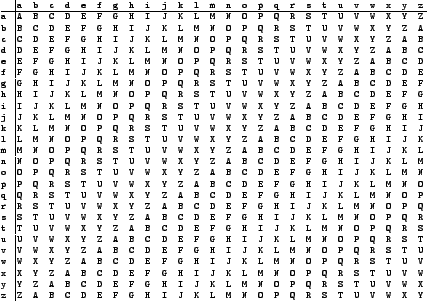

In the following table, it is shown what number corresponds to each character in ASCII:

The ASCII includes all the characters that are used in the English language. For other languages, there is a bigger character set called Unicode.

For example, in the ASCII table, you can see that the @ symbol is represented as the 64 number in decimal.

The table also has a column called Hx or Hexadecimal, which is base 16. Decimal is base 10.

The decimal base is the one we use in everyday life, which likely comes from the fact that humans have 10 fingers. Therefore, we have 10 different symbols to represent all different numbers. In computers, it is helpful to have a base with 16 symbols because it translates easier to binary. You probably know that most computers physically store only binary numbers, which are represented only by 0 and 1. A binary digit is called a bit. Although computers use binary, base 16 is easy to translate from binary for us humans.

The hexadecimal base (or base 16) has the following symbols:

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 a b c d e fThe binary base (or base 2) has these symbols:

0 1The decimal base (or base 10), has the following symbols:

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9Let’s see in python how can we use the hexadecimal representation to print characters. In a python string, you can put “\x” which is a special sequence to tell python that the following two characters are a hexadecimal number:

print("picoCTF")

print("\x70\x69\x63\x6f\x43\x54\x46")When you run that program you should see:

picoCTF

picoCTFCheck the table to see that the characters match!

As a challenge, print the string “I_LOVE_PICOCTF” only using hexadecimal. Note that uppercase letters are represented by a different hexadecimal number than lowercase letters.

4.8. Pwntools

For binary exploitation, there is a very useful library called pwntools:

Keep this library in mind as an important part of python for exploitation. You do not need to learn anything right now. We will teach how to use it in binary exploitation.

4.9. Http requests in python

Below is an example of how you can request a web page in python. Here we are requesting the HTML of the picoCTF website. Right now, maybe you do not know HTML and worry this will not make much sense to you. After you are done with the Web section, come back here and try this example:

import http.client

conn = http.client.HTTPSConnection("picoctf.org")

conn.request("GET", "/")

r1 = conn.getresponse()

print(r1.status, r1.reason)

# 200 OK

data1 = r1.read()

conn.request("GET", "/a")

r2 = conn.getresponse()

print(r2.status, r2.reason)

# 404 Not Found

data2 = r2.read()

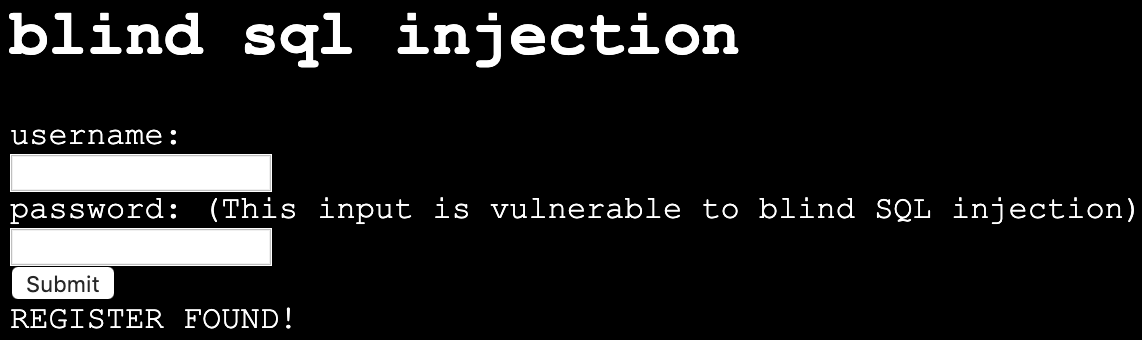

conn.close()5. Web Exploits

Samuel Sabogal Pardo

Web exploits are a nice starting point to dive into the world of hacking. Chances are that you are familiar with a web browser, so you will feel you are working on something that you already know!

5.1. Html

Before diving into Web Exploits, you need to understand how a website works. Many years ago, the web was used to visit static pages that did not have interactive features; they just showed information. To do a static page, it is enough to write some lines of HTML. What is HTML? First, it is not a programming language. Html means HyperText Markup Language, and we use it to determine the font size, colors, margins, or similar features in a web page. When an html file is accessed in a browser like Firefox, Chrome or whichever browser you like, the browser presents the text according to the html on it. Your browser can access an html file locally. Locally means that the file could be in your laptop or file system. In contrast, it could access the file remotely through the Internet. Let’s see an example of creating a simple html and access it locally:

-

On your computer, create a folder called "picoexample" and then, inside that folder, create a text file and name it "myFirstPage.html". You can do this on Notepad on Windows, Textedit on Mac, or any text editor from Linux. It is important that the extension is ".html". It cannot be ".html.txt" or something that is not exactly ".html". If you don’t see the extension in your operating system, this is a good opportunity to google how to make it appear to be able to modify it. Remember, for obstacles that might appear along the way, google is the answer.

-

Edit the content in a text editor and write: Hello World!

-

Save the file

-

Open the file in any browser. To do that, you can right click on the file, and then select "open with" and choose the browser you want. You should see a page like the following:

-

Now, in the text editor, modify the content of the file and replace the text by: <b>Hello World!</b>

-

Save the file on the text editor. Then, open the file in the browser again, or you can simply click refresh on your browser. Since it already has opened the file, you will see the message in bold, similar to this:

You just created a page with a very simple HTML that made your message appear in bold. Note that <b> is the opening tag, </b> is the closing tag. Analyze the difference between the opening and closing tag. What do you see? The closing tag is usually the same as the opening tag, but you include "/" like we just did. We just used an html tag to tell the browser we want some specific text in bold. Html is just a bunch of tags that allow us to do similar things.

Now let’s make a page with more fields so you can get a sense of tags and the structure of a bigger page. Use the following HTML code to replace the content of the file you are editing:

<html>

<head>

<title>This is a picoCTF html Example</title>

</head>

<body>

<h1>This is a Heading</h1>

<h2>This is a smaller Heading</h2>

<p>This is a paragraph.</p>

The following is an image:<br>

<img src="picologo.png" />

</body>

</html>As you did before, save the file in the text editor and click refresh on the browser. You probably see something like this:

If you read the html code and try to analyze its content, you will realize the following:

-

The title shown in that tab of the browser "This is a picoCTF html Example", appears there because you put that text inside in the <title></title> tags.

-

<h1> Is used to create a big heading

-

<h2> creates a heading smaller than <h1>

-

The <head> tags are used to group introductory content, in this case the title, but if you remove this tag, you will not see much change in our page. Do the experiment of removing it. If you only remove the opening or closing tag it will cause an html error, so make sure to delete the opening tag and closing tag.

-

The <body> tags are used to group the main content of the page. If you remove them you will not see much change in our page because we have just a few things. However, in several cases you might break a page completely if you remove a tag without proper care.

You may have noted the <img> tag is not showing any image as it should. Why? Let’s analyze the element img:

<img src="picologo.png" />First you see there is not opening or closing tag, there is just one tag with the slash at the right-hand side. This is ok for an image. As you can see, it has an attribute called "src", which means source. We are assigning to "src" the value "picologo.png". Our html is going to try to access a file called "picologo.png" in the same folder where "myFirstPage.html" is contained, which is the folder we name at first "picoexample". There is no image called "picologo.png", so the browser has nothing to show. Copy and paste an image to the folder and name it "picologo.png". The extension of the image has to be ".png". If you have an image with a different extension, you can just use the extension you need in the "src" attribute in your html. For example, if the extension of the image you have is ".jpg" you can simply replace

<img src="picologo.png" />with

<img src="picologo.jpg" />If you successfully created the image in the folder, and refresh the browser you will see the following, of course, with your own custom image:

A fundamental part of web sites are the links. The link tag is <a>, the following is an example of a link directed to google:

<a href="http://google.com" > Go to google! </a>Use that element and put it in your code to make a link to the web site you want. Now practice by adding more html tags and images in your page! This is a reference in which you can find more html tags:

5.2. JavaScript

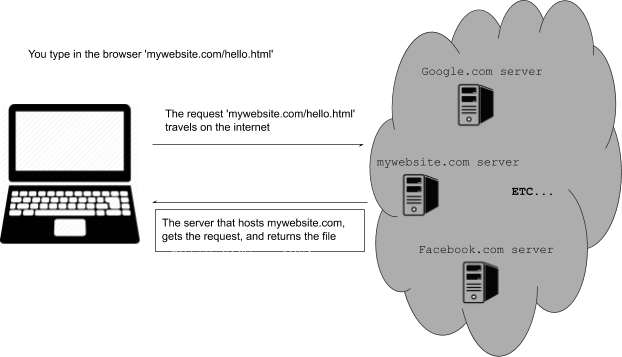

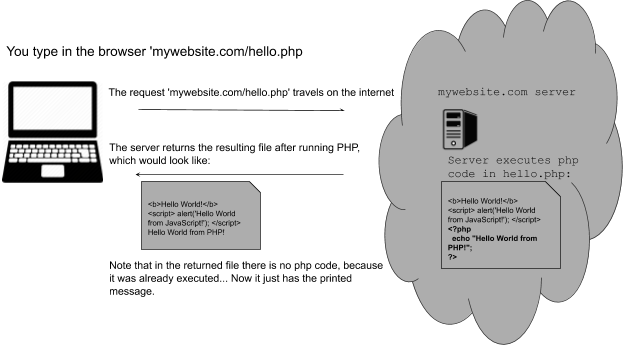

To make pages more interactive JavaScript is commonly used. JavaScript is a programming language! We can do algorithms using it. JavaScript is executed in your browser. For example, when you visit a website, the JavaScript code is downloaded along the HTML and it only executes once it is loaded in your browser. When you visit a page, you are downloading an html file and your browser interprets the tags and prints the text and images as we learned before. This image illustrates that process:

If that file happens to contain JavaScript, your browser will execute it. Let’s look at an example. In the same folder "picoexample", create a file called "myFirstJS.html" using a text editor. Then, put the following content in the file:

<html>

<head>

<title>This is a picoCTF JS Example</title>

<script>

alert("Hello picoCTF");

</script>

</head>

<body>

<h1>JavaScript example</h1>>

</body>

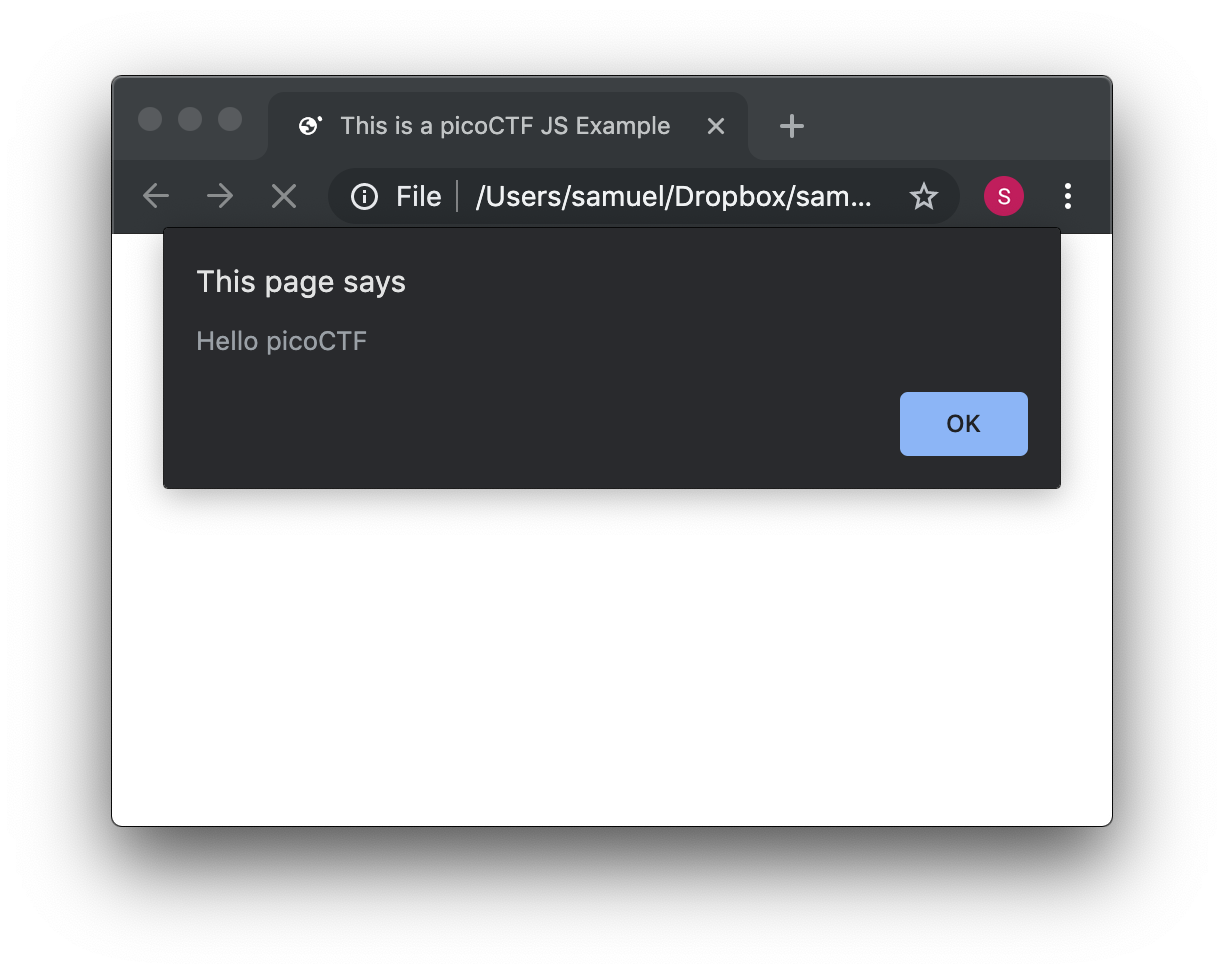

</html>Save the file. As soon as you open the page, you will see an alert showing "Hello picoCTF", something like this:

If you analyze the file, you will note that the magic is happening in this element:

<script>

alert("Hello picoCTF");

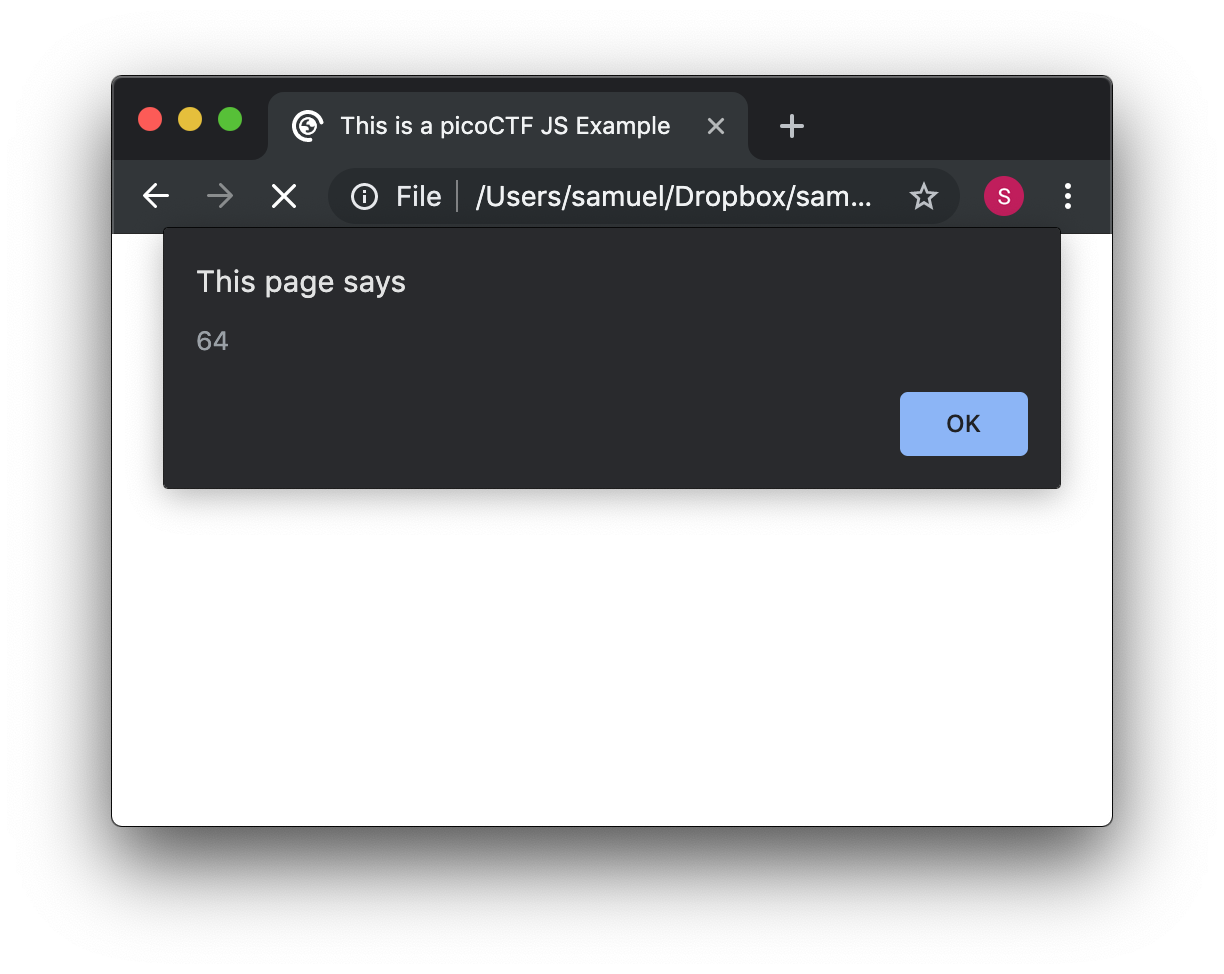

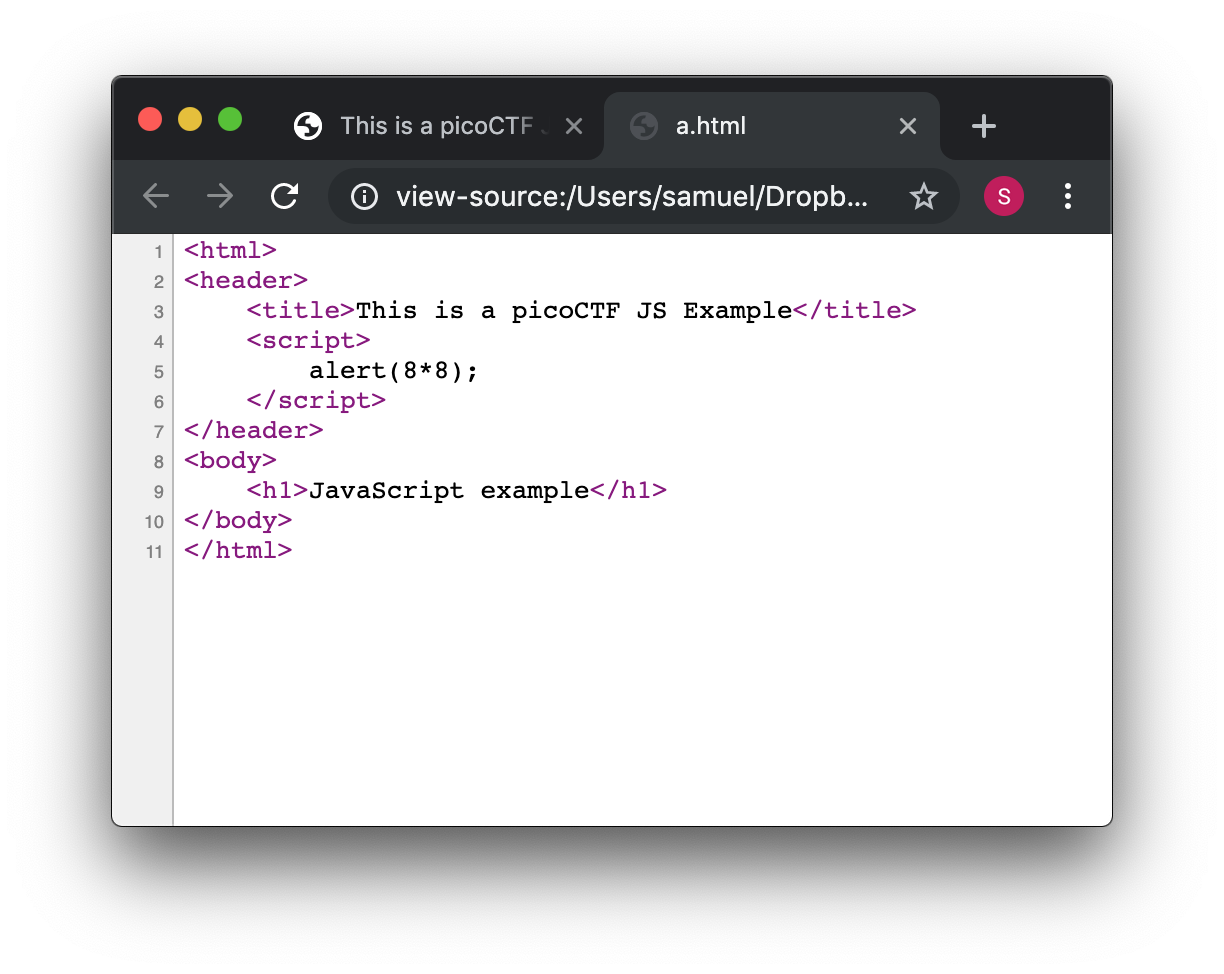

</script>Whatever you put inside the tags "<script> </script>" will be tried to execute by the browser as JavaScript. Since JavaScript is a programming language, we should be able to do some arithmetic. Replace the string "Hello picoCTF" by an arithmetic operation, like 8*8, like this:

<script>

alert(8*8);

</script>Note that we only use quotes when we want to use a string. In arithmetic operations we don’t use quotes. Save the file and refresh the browser. You should see the following:

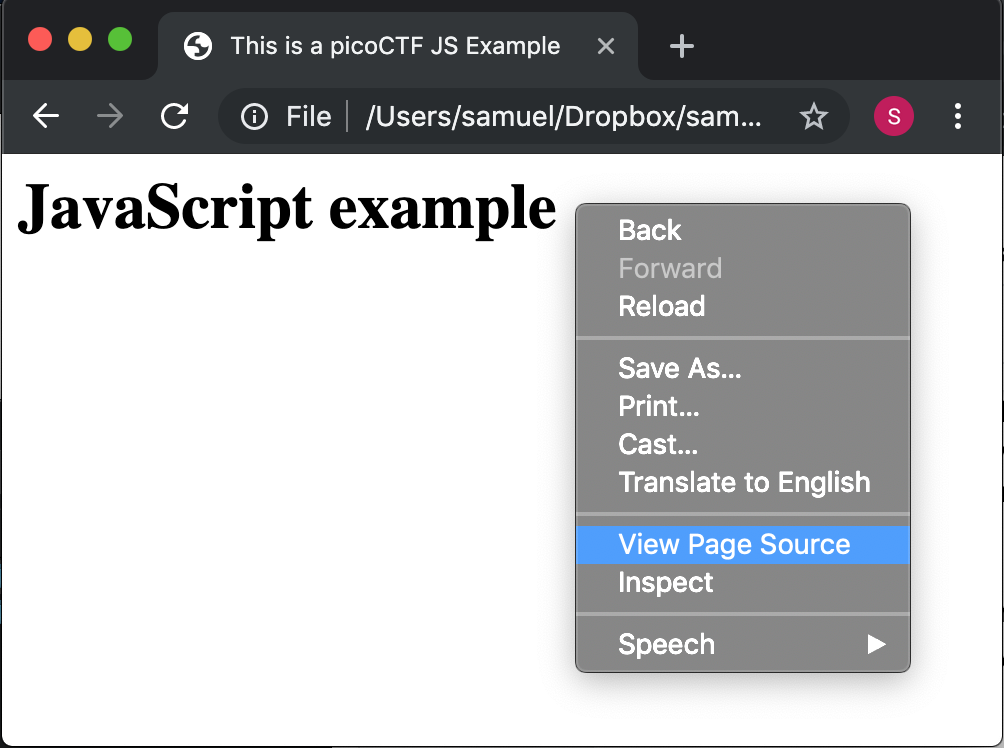

Click Ok in the alert message to make it go away. Anything you write in JavaScript or html will be visible for any user that accesses your page in a browser. To see the html and JavaScript code in your browser right click the page and then "View Page Source"

You will see the JavaScript code you just wrote:

This is a very important thing! Never put a secret in your JavaScript code or html. If someone does it, that will be a vulnerability in your page. As a hacker you can try to look for secrets on the html of a page you want to exploit.

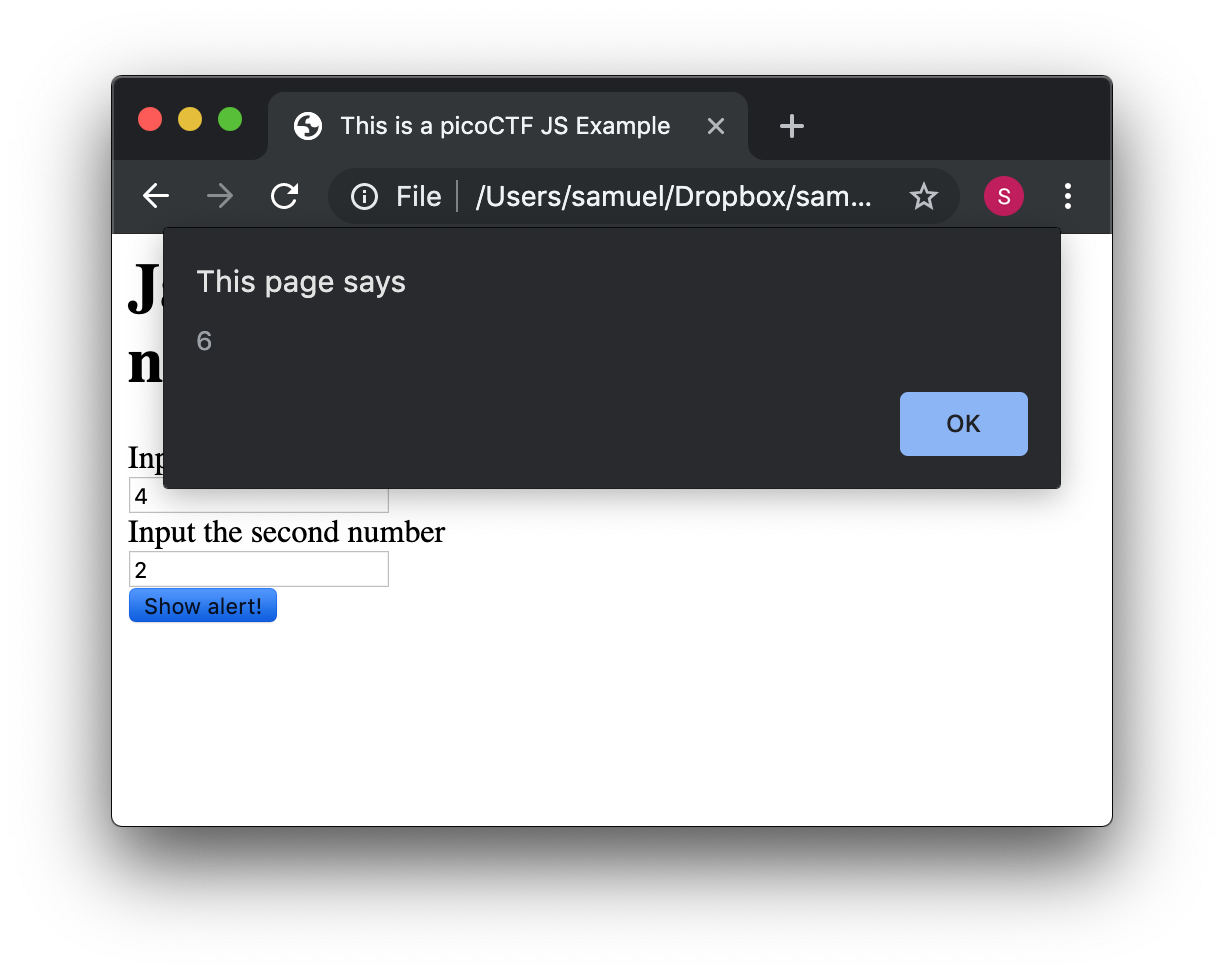

Now let’s use some more elaborated code. We are going to make a page that adds two numbers input by the user and shows the result in an alert. We will explain its code in detail later. The code is the following: